- NATIVELY COMPILED LANGUAGE; straight to machine code.

- C sharp and java are compiled in a virtual environemtn?

Doesn’t run as fast as other compiled, but compiles (builds) more quickly

package main

Write a function to print Hello world to the console in Go.

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

fmt.Println("hello world")

}Go code generally runs ____ than interpreted languages and compiles ____ than other compiled languages like C and Rust

main.go -> go build -> myprogram.exe

- can run the executable without having Go, doesn’t even know was made with Go.

- Different to python - need python interpreter

On bootdev

- Code gets shipped to serve, compiled, run.

- Compiler vs. Runtime error

processors are not chatGPT< they need machine code.

how to distribute python code vs. compiled code

main.py (interpreted) - give your friend main.py and on their computer they run python main.py

friend needs python installed on computer (dependent) - need to know how to use a command line

main.go -> compile, then you can sell, without giving away the source code.

Do users of compiled programs need acess to source code? (Hypotheticals) - Mai

- compiled binaries are good (also in servers)

- strong and static typing

- when you declare a string = “wagslane” can’t accidentally be changed later

- we find bugs in compilation instead of running (compile time error)

Drums in the background.

- can do operatioin with consts as long as they can be known at compile time.

Function signature: func concat(a string, b string) string {

strongly vs statically typed

- Strong vs Weak Typing:

Strongly typed

In strongly typed languages, the compiler prevents you from mixing different kinds of data together. This is limiting, but can be very helpful when you want to avoid putting a string, say, into the floating point value for the altitude of an airplane’s automatic pilot.

- Strongly typed languages enforce strict type rules, making implicit type conversions rare.

- Weakly typed languages allow more flexibility in type handling, often performing implicit type conversions.

-

-

Static vs Dynamic Typing:

- Statically typed languages require variable types to be declared at compile-time, and once a variable is defined as a specific type it cannot be changed in the future

- Dynamically typed languages determine variable types at runtime, and type checking is performed during execution.

Camel case vs. snake case Callback: a function that can be passed to another function to be called later.

func f(g func(int, int) int, n int) int

f func(func(int, int) int, int) int

Memory:

by value (unless explicitly..) vs. by reference

-

GO does not allow unused variables

-

implicit naked returns = bad

-

named returns

early returns / gaurd clauses

- they provide a linear approach to lgic trees.

nil error

heuristic used by developers

- struct is first of the collection types: a type that contains other types.

- dictionairy

type car struct {

Make string

Model string

Height int

Width int

FrontWheel Wheel

} - statically typed language; types must be inferred or specified, and they cannot change.

var myVariable stringorvar myvariable = "string" - strongly typed: operation you can perform on variable depends on its type. Compiler can do more thorough debugging

- GO is compiled - binary machine code file. Python is interpreted.

- Fast compile time

- Built in concurrency: no packages needed (parallelism, goroutines)

- Simplicity; garbage collection - frees up unused memory

https://youtu.be/8uiZC0l4Ajw?si=gP8N0BiabYE0GgIp

package main

go build

go run

package main

import ("errors"

"fmt")

func main() {

var printValue = "i don't know what to do"

printMe(printValue)

}

func printMe(printValue string) {

fmt.Println(printValue)

}

func intDivision(numerator int, denominator int) (int, int) {

var result int = numerator/denominator

var remainder int = numerator%denominator

return result, remainder

}

default value 0, int-error

lazy evaluation

switch{

case err!=nil:

case remainder==0:

default

}

// conditional switch statement

switch remainder{

case err!=nil:

case remainder==0:

default

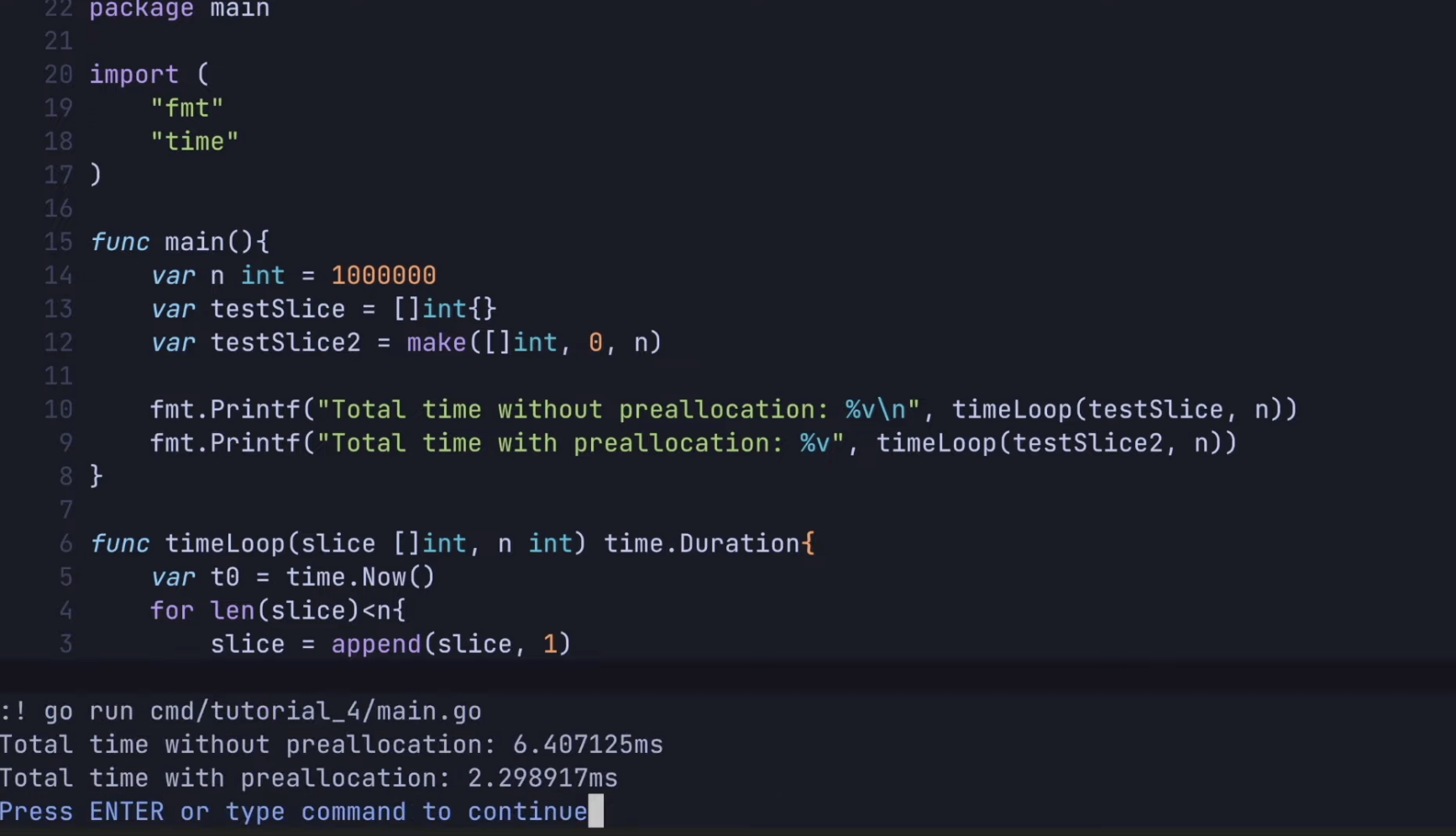

}ARRAYS fixed length same type indexable continguous in memory

func main(){

var intArr [3]int32 // 12 bytes

}

fmt.Println(&intArr[0])

fmt.Println(&intArr[1]) // +4

fmt.Println(&intArr[2]) // +4

intArr := [...]int32{1, 2, 3}slices are just wrappers around arrays

var intSlice []int32 = []int32{4, 5, 6}

fmt.Println(intSlice)

intSlice = append(intSlice, 7)

fmt.Println(intSlice)

len() and cap()

var myMap map[string]uint8 = make(map[string]uint8)for i<10{

}

for i, v := range intArrP{

}

for i:=0,

Strings

Structs

type gasEngine struct{

mpg uint8

gallons uint8

}

myEngine gasEngine = gasEngine{25, 15}

type ___ struct {

name string

int <- nested

}

// methods

func (e gasEngine) milesLeft() uint8 {

return e.gallons*empg

}Interface: just need same type and methods

type engine interface {

}

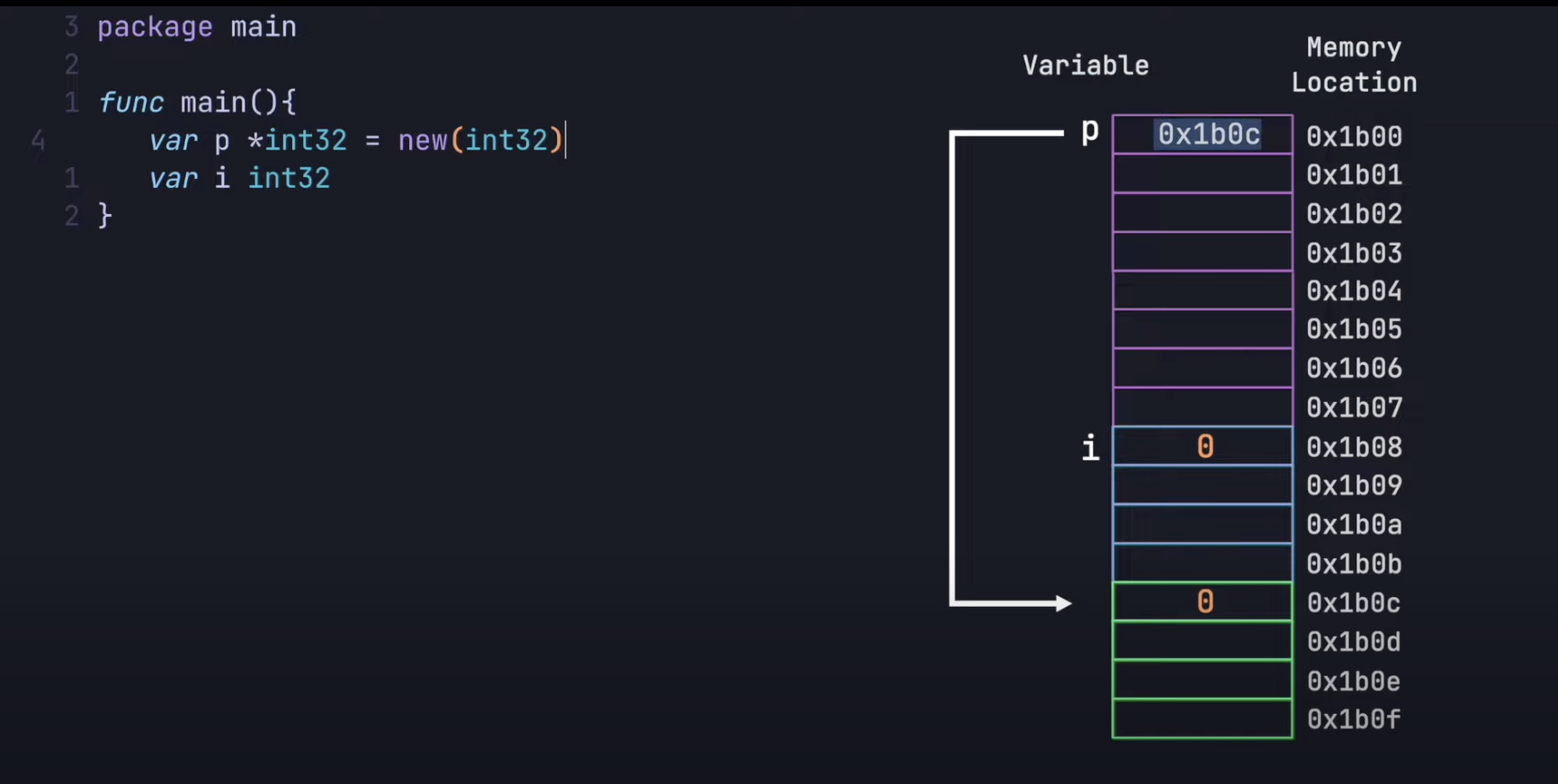

Pointers: type, which store memory addresses (that’s all)

func main(){

var p *int32 = new(int32)

var i int32

}

//0x means: about to be hexadecimal

32 bit or 64 bit, 4 or 8 depending on system, * means CREATE POINTER (DOUBLE SOMETHING) * means SET THE VALUE AT THE MEMORY LOCATION THIS POINTER POINTERS TO

a memory address must be assigned (malloced) to the pointer

&i refers to the memory address of i not it’s value.

pass by reference or pass by value

myLiat = [5]uint32{1, 2, 3, 4, 5}Concurrency ≠ Parallel Execution (all the time)

- multiple tasks in progress (can switch from task, if one is loading)

- parallel execution is having 2 cpu cores wokring on both tasks

func myFunc(){

}

go myFunc()WaitGroups are just counters. Whenever you spawn a new go routine, add 1 to the counter, then decremtent with wg.Done()

wg.Wait() wait till it’s 0. it’s a stack. multiple thread s modifying same memory location at once